A new champion has emerged in the world of timekeeping. Scientists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have set a new record for clock accuracy with their upgraded atomic clock, which uses a single aluminum ion trapped and measured with extreme precision. Part of the latest generation of optical atomic clocks, this device can measure time to an astonishing 19 decimal places.

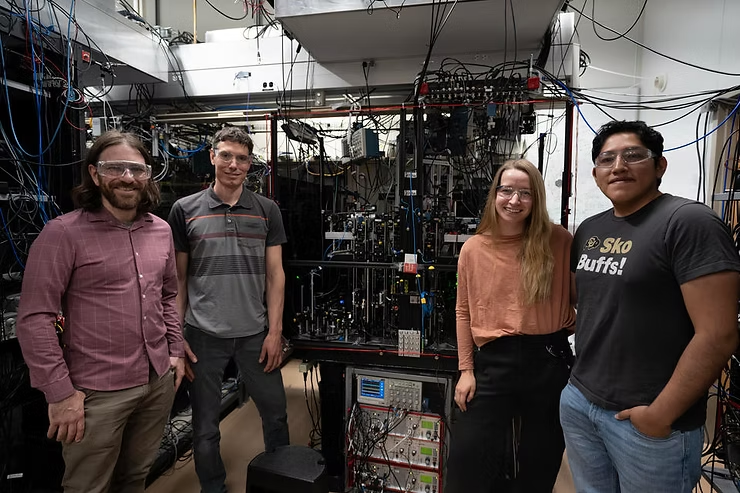

Optical clocks are judged on two key criteria: accuracy—how closely they align with the true definition of time—and stability, which reflects how consistently they measure time over intervals. This new aluminum ion clock outperforms all previous clocks on both fronts. It’s not only 41% more accurate than the previous record-holder but also 2.6 times more stable than any other ion-based clock to date. Achieving this breakthrough required fine-tuning every component, from the lasers and ion trap to the vacuum system that houses the entire setup.

“It’s exciting to work on the most accurate clock ever,” said Mason Marshall, a NIST physicist and lead author of the study. “Here at NIST, we have the opportunity to pursue long-term precision measurement projects that help advance physics and deepen our understanding of the universe.”

The aluminum ion is an ideal candidate for precision timekeeping. It “ticks” at an extremely stable, high-frequency rate—more reliably than cesium, the element currently used to define the official length of a second, according to David Hume, the NIST physicist leading the project. It’s also less affected by external factors like temperature changes and magnetic fields, making it especially dependable.

But working with aluminum ions isn’t easy. “Aluminum is a bit shy,” explained NIST researcher Mason Marshall. It doesn’t respond well to the laser techniques required to cool and measure atoms in an atomic clock. To overcome this, the team used a clever workaround: pairing the aluminum ion with a magnesium ion. Unlike aluminum, magnesium can be easily manipulated with lasers. “This ‘buddy system’ is known as quantum logic spectroscopy,” said graduate student Willa Arthur-Dworschack.

READ ALSO: Anduril Unveils Seabed Sentry: A New Underwater Sensor Network

In this system, magnesium cools the aluminum ion and helps scientists read its state by syncing its movements with its aluminum partner. Even with this pairing, fine-tuning the system involved tackling a number of complex physical challenges, noted graduate student Daniel Rodriguez Castillo.

“One of the biggest challenges was designing the ion trap,” Castillo explained. The trap was causing subtle unwanted movements in the ions—known as excess micromotion—which reduced the clock’s precision. These movements were the result of tiny electrical imbalances in the trap that disrupted the ions’ ticking. To fix this, the team redesigned the trap by placing it on a thicker diamond wafer and improving the gold coating on the electrodes. These adjustments reduced electrical resistance and balanced the electric fields, allowing the ions to stay still and tick with minimal interference.

The team also had to solve a major issue with the clock’s vacuum system. According to Marshall, standard steel vacuum chambers slowly release hydrogen gas, which can interfere with the delicate ion trap by colliding with the ions and disrupting their function. This limited how long the clock could run before the ions had to be replaced—roughly every 30 minutes. To fix the problem, the team built a new vacuum chamber out of titanium, which reduced background hydrogen levels by a factor of 150. With this change, the trap could run for days without needing to be reloaded.

READ ALSO: AI helps couple conceive after 18 years of failed attempts with breakthrough approach

READ ALSO: Study reveals Arabia’s rainfall was five times more extreme 400 years ago

But there was still one more crucial upgrade needed: a more stable laser to probe the ions and measure their ticking. The 2019 version of the aluminum ion clock had to run for weeks just to average out the quantum noise—random fluctuations in the ions’ energy levels—caused by laser instability. To overcome this, the team collaborated with Jun Ye at JILA, a joint institute of NIST and the University of Colorado Boulder. Ye’s lab is home to one of the most stable lasers in existence and is known for developing the strontium lattice clock that previously held the world record for accuracy.

It was a highly collaborative effort. Ye’s lab transmitted the ultrastable laser signal via fiber-optic cables running beneath the streets—over a distance of 3.6 kilometers (just over 2 miles)—to Tara Fortier’s lab at NIST. There, a frequency comb, which functions like a ruler for measuring light frequencies, was used to compare Ye’s laser with the aluminum clock’s laser. This allowed the aluminum clock to adopt the exceptional stability of Ye’s laser.

Thanks to this enhancement, the researchers could now probe the aluminum ions for a full second—up from just 150 milliseconds—dramatically improving the clock’s performance. As a result, the time needed to measure down to the 19th decimal place was cut from three weeks to just a day and a half.

With this new achievement, the aluminum ion clock plays a key role in the global push to redefine the second with far greater precision, opening the door to scientific and technological breakthroughs. The recent upgrades also make it a powerful platform for quantum logic experiments, helping researchers explore new ideas in quantum physics and develop the next generation of quantum technologies—an exciting opportunity for everyone involved.

Even more significantly, the reduced averaging time—from weeks to just days—means the clock can now be used for advanced applications like measuring subtle shifts in Earth’s shape and gravity (geodesy), or testing bold new theories in physics. These include investigating whether the so-called “fundamental constants” of nature might actually be slowly changing over time.

“With this platform, we’re in a great position to explore new clock designs—like increasing the number of ions or even entangling them—which could push our measurement capabilities even further,” said Willa Arthur-Dworschack.