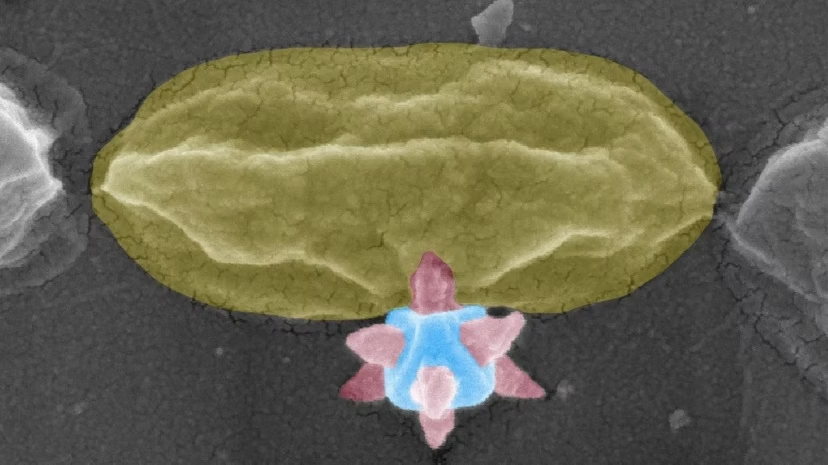

Credit: Zhejian Cao, Chalmers University of Technology

Chalmers University of Technology researchers have pioneered a new weapon against dangerous bacterial biofilms: a coating made from metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) that physically impales and kills bacteria without antibiotics. Led by study lead author Zhejian Cao, PhD in Materials Engineering, the innovation uses the very material class that won the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, applying it in a novel mechanical mechanism to combat infections on medical implants and devices.

Bacterial biofilms—slimy, protective communities that form on surfaces—are a relentless problem in healthcare, clinging to catheters, hip replacements, and dental implants. These biofilms are notorious for causing hospital-acquired infections that lead to immense suffering, skyrocketing costs, and accelerated antibiotic resistance. Traditional solutions often rely on chemicals or toxic metals, but the Chalmers University team has developed a purely physical, mechanical killer.

The breakthrough centers on growing one MOF on top of another to create a surface studded with sharp nanotips. When bacteria approach this coated surface, these nanostructures act like microscopic spikes, puncturing the bacterial cell membranes and causing them to die.

“Our study shows that these nanostructures can act like tiny spikes that physically injure the bacteria, quite simply puncturing them so that they die,” explained Zhejian Cao. This mechanical action represents a fundamental shift from previous approaches that depended on leaching toxic ions.

READ ALSO: https://www.modernmechanics24.com/post/tibet-dung-microbes-transform-biotech

One of the most critical challenges was engineering the perfect spacing between these nanotips. If the gaps were too wide, bacteria could slip through unharmed and attach to the surface. If they were too close together, the principle behind a “bed of nails” would apply—distributing the force and allowing bacteria to survive. The researchers had to find the Goldilocks zone where the spacing maximizes lethal puncturing force. “It’s a completely new way of using such metal-organic frameworks,” stated Zhejian Cao, highlighting the novelty of their approach.

A significant advantage of this MOF coating is its compatibility with various surfaces and its potential for integration into other materials. Since it kills bacteria mechanically, it eliminates the need for antibiotics or toxic biocides, directly addressing the global crisis of antimicrobial resistance.

“It fights a major global problem, as it eliminates the risk that controlling bacteria will lead to antibiotic resistance,” added Zhejian Cao. This makes it exceptionally valuable for medical devices, where preventing initial bacterial attachment can stop infections before they start.

WATCH ALSO: https://www.modernmechanics24.com/post/us-marines-seaglider-rescue-showcase

The research was a collaborative effort between two teams at the university: Professor Ivan Mijakovic’s and Professor Lars Öhrström’s. Professor Öhrström, a co-author with three decades of experience in MOFs, emphasized the practical benefits for scaling this technology.

Unlike previous antibacterial nanostructures like graphene, which require high-temperature manufacturing, these MOF coatings can be produced at lower temperatures. This makes them suitable for temperature-sensitive materials like the plastics commonly used in medical implants.

Furthermore, the organic components of these MOFs can potentially be sourced from recycled plastics, aligning the technology with circular economy principles. “This facilitates large-scale production and makes it possible to apply the coatings to temperature-sensitive materials,” said Professor Lars Öhrström. The potential for large-scale, sustainable manufacturing positions this innovation for real-world impact beyond the laboratory.

READ ALSO: https://www.modernmechanics24.com/post/tibet-dung-microbes-transform-biotech

The implications extend far beyond healthcare. Biofilms plague ship hulls, leading to biofouling that increases fuel consumption, and they clog industrial pipes, causing corrosion and inefficiency. Current antifouling paints often leach toxic substances into the environment. This MOF coating offers an eco-friendly alternative by providing a physical, non-toxic barrier.

By repurposing a Nobel Prize-winning material for a groundbreaking application, the Chalmers University team has opened a new front in the fight against bacteria. This research demonstrates that sometimes the most effective solutions aren’t chemical, but physical—turning surfaces into microscopic battlefields where bacteria meet their end on a forest of tiny, lethal spikes.

WATCH ALSO: https://www.modernmechanics24.com/post/slac-quest-for-perfect-fusion-fuel