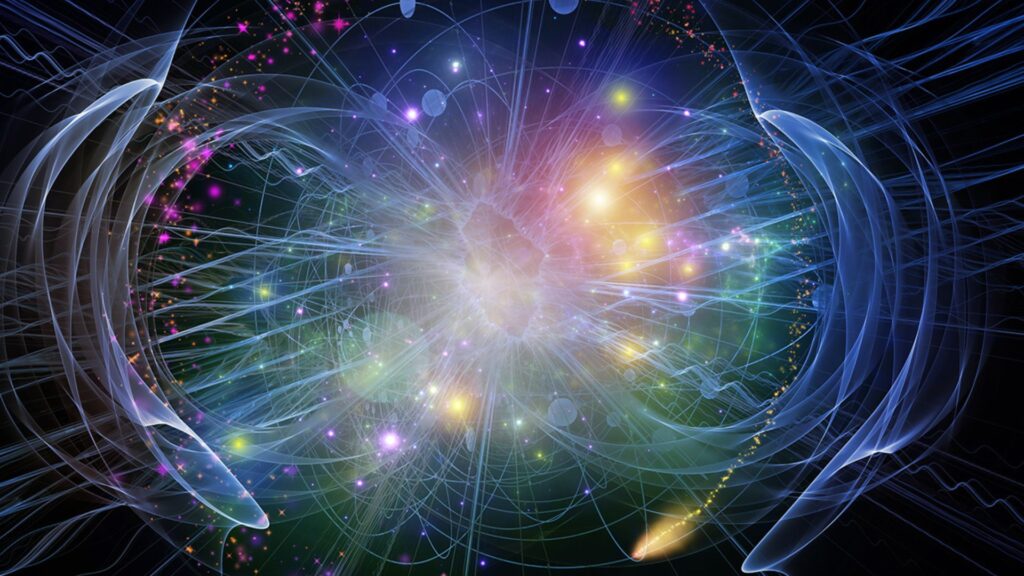

Ohio University researcher Lawrence Witmer has co-authored a groundbreaking study revealing that pterosaurs and birds developed the neurological capacity for flight through entirely different evolutionary pathways. Published in Current Biology, the research shows pterosaurs achieved powered flight with surprisingly modest brain sizes, challenging long-held assumptions that complex flight requires large brains.

The study represents a research homecoming for Professor Witmer, who first explored pterosaur neuroanatomy in a seminal 2003 Nature paper. “We’ve had abundant information about early birds and knew they inherited their basic brain layout from their theropod dinosaur ancestors,” said Witmer, a professor of anatomy at the Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine. “But pterosaur brains seemed to appear out of nowhere. Now, with our first glimpse of an early pterosaur relative, we see that pterosaurs essentially built their own ‘flight computers’ from scratch.”

The breakthrough came from examining Ixalerpeton, a small lagerpetid archosaur that lived 233 million years ago in what is now Brazil. This creature represents the closest known relative to pterosaurs, providing scientists with their first clear window into the neurological starting point of pterosaur evolution. “The breakthrough was the discovery of an ancient pterosaur relative,” said lead author Mario Bronzati, an Alexander von Humboldt fellow at the University of Tübingen in Germany.

Using advanced microCT scanning technology, the international team created detailed 3D reconstructions of brain structures from more than three dozen species, including pterosaurs, early dinosaurs, modern birds and crocodiles, and various Triassic archosaurs.

READ ALSO: https://www.modernmechanics24.com/post/soft-composite-symmetry-breaks-smart-tech

“Then, using statistical analysis of the size and 3D shape of their cranial endocasts, we were able to map the stepwise changes in brain anatomy that accompanied the evolution of flight,” explained coauthor Akinobu Watanabe, associate professor of anatomy at the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine.

The analysis revealed that while both pterosaurs and birds developed enhanced visual processing capabilities, their neurological adaptations diverged significantly. Ixalerpeton showed some pre-adaptations for flight, including an enlarged optic lobe for improved vision, but lacked the specialized brain structures that would later characterize pterosaurs. Most notably, pterosaurs developed a greatly enlarged flocculus – a cerebellum structure that processes sensory information from wings to stabilize vision during flight. This feature was completely absent in their lagerpetid relatives.

Perhaps the most surprising finding was that pterosaurs managed their aerial feats with relatively small brains. “While there are some similarities between pterosaurs and birds, their brains were actually quite different, especially in size,” said coauthor Matteo Fabbri, assistant professor of Functional Anatomy and Evolution at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “Pterosaurs had much smaller brains than birds, which shows that you may not need a big brain to fly.”

WATCH ALSO: https://www.modernmechanics24.com/post/elon-musk-space-internet-ghana

The research demonstrates two distinct evolutionary routes to flight: birds inherited brains that were already partially pre-adapted from their dinosaur ancestors, while pterosaurs essentially built their flight neurology from the ground up. The larger brains seen in modern birds likely developed later and were tied more to enhanced cognition and complex behaviors rather than the mechanical demands of flight itself.

The study underscores the continuing importance of paleontological fieldwork in reshaping our understanding of evolutionary history. “Discoveries from southern Brazil have given us remarkable new insights into the origins of major animal groups like dinosaurs and pterosaurs,” said coauthor Rodrigo Temp Müller, a paleontologist at Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Brazil. With each new fossil, scientists continue to rewrite the story of how ancient creatures conquered the skies through different but equally effective evolutionary strategies.

READ ALSO: https://www.modernmechanics24.com/post/lithium-waste-into-super-strong-concrete