What if everything we thought we knew about manufacturing metals was slightly off? MIT researchers just uncovered something that’s been hiding in plain sight for decades—and it challenges a fundamental assumption about how metals behave.

Here’s the surprising part: No matter how much you heat, roll, or deform a metal alloy, you can never completely randomize its atoms. Scientists assumed that intense manufacturing processes would shuffle atoms into complete chaos, like shaking a snow globe until everything settles randomly. Turns out, that’s not what happens at all.

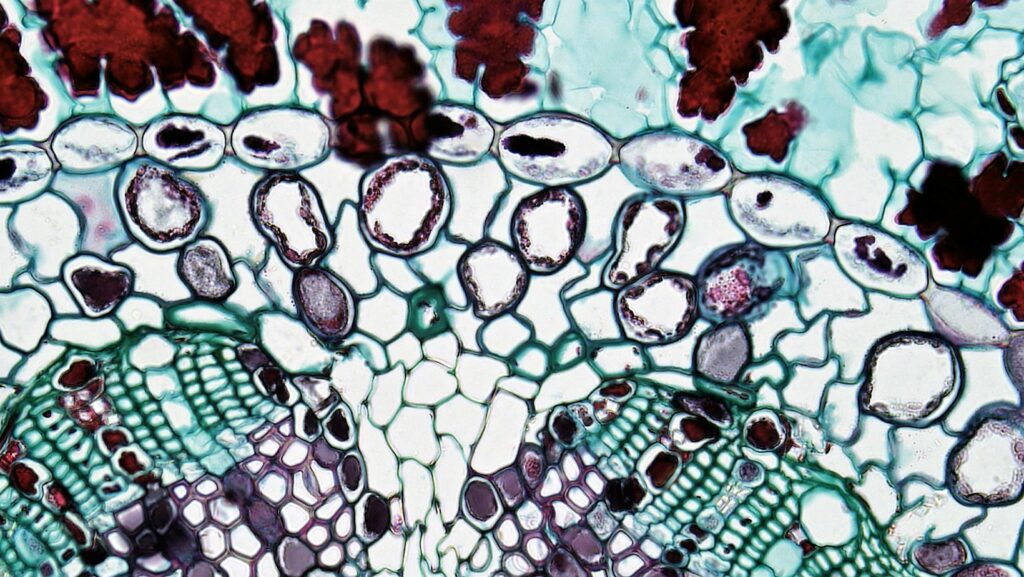

Rodrigo Freitas and his team at MIT set out to answer a straightforward question about how fast chemical elements mix during metal processing. They used machine-learning techniques to track millions of atoms as they moved through conditions that mimicked real-world manufacturing. What they found stopped them in their tracks.

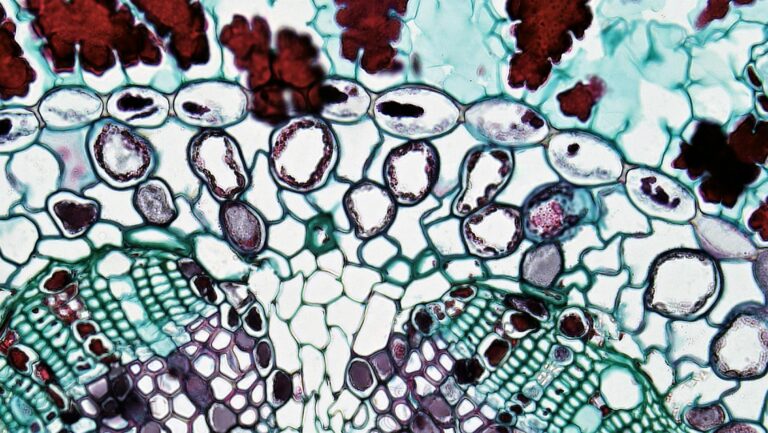

Even after extreme processing—the kind of violent deformation and heating that should thoroughly scramble everything—subtle chemical patterns persisted. These weren’t just laboratory curiosities either. The team discovered these patterns exist in conventionally manufactured metals all around us.

READ ALSO: https://www.modernmechanics24.com/post/how-bird-species-forage-together-in-antarctica

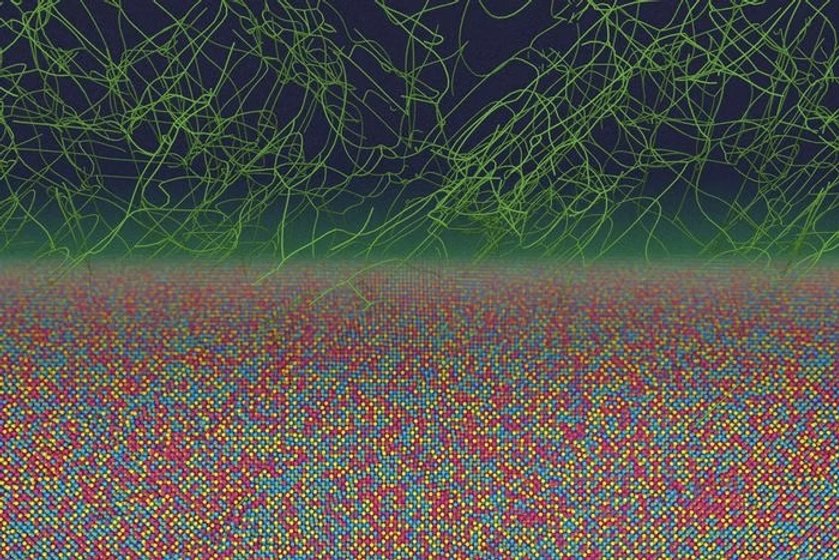

The breakthrough reveals a new physical phenomenon. As metals are deformed, defects called dislocations act like three-dimensional scribbles within the material. When these scribbles warp and shuffle nearby atoms, they’re not doing it randomly. They have chemical preferences, taking the path of least resistance by breaking weaker bonds over stronger ones. This creates what researchers call “far-from-equilibrium states”—patterns never seen outside manufacturing processes.

Think of it like this: Your body maintains a steady temperature despite external conditions constantly changing. Metals do something similar, balancing an internal push toward disorder with an ordering tendency that favors certain atomic arrangements.

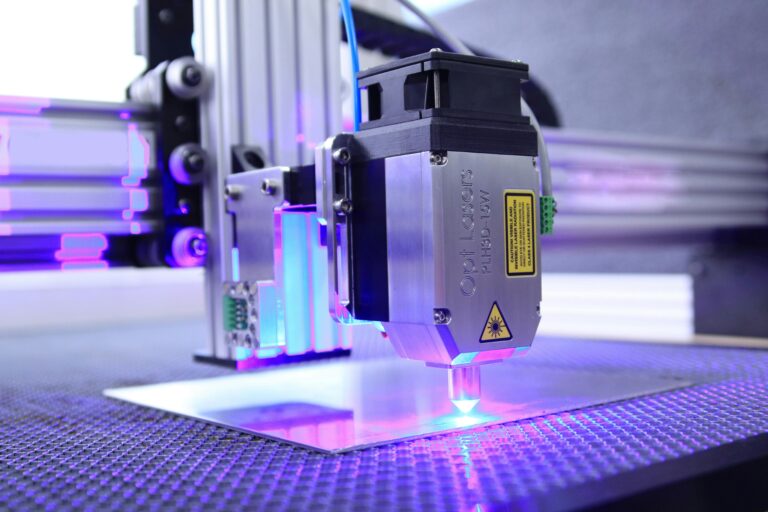

Why does this matter? These chemical patterns affect everything from mechanical strength and durability to radiation tolerance and catalytic properties. Industries from aerospace to nuclear reactors could use this discovery to tune metal properties during production rather than leaving it to chance.

WATCH ALSO: https://www.modernmechanics24.com/post/sweden-tests-self-driving-truck-in-europe

As Freitas puts it, “Right now, this chemical order is not something we’re controlling for or paying attention to when we manufacture metals.” That’s about to change.